– Ricci Churchill, DBCT

Have you ever seen the “Dugong Sanctuary” signs on the Bruce Highway near Clairview and wondered what they mean?

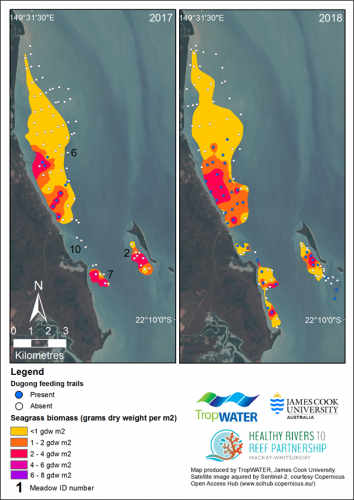

In 1997, the Great Barrier Reef Ministerial Council established Clairview as a dugong sanctuary. Dugongs feed on the seagrass meadows and come to the surface when they breathe.

On Saturday 28 September I drove down to the Barra Crab Caravan Park at Clairview to meet the scientists from James Cook University to help them monitor and measure the seagrass extent at low tide. The monitoring program is part of the Waterway Health Report card the Mackay Whitsunday Healthy Rivers 2 Reef Partnership produces, which DBCT is a proud financial partner.

The monitoring is undertaken via helicopter – without doors – at very high speeds and just inches off the sand/water!

When I arrived, the pilot straightaway sized me up and asked if I really needed whatever was in my backpack. Any extra weight meant less fuel which meant less time seagrass monitoring. My back pack was left behind.

After a safety debrief where we reviewed the risks and talked about the outcome of each hazard being realised could be permanent injury or death, we then strapped on our lifejackets, earphones with microphone and buckled our seat belts!

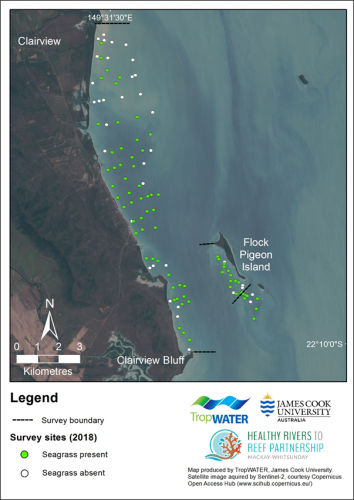

Our first job was to map the seagrass extent. This was done with a scientist watching a laptop for GPS coordinates while directing the pilot, which meant lots of sharp banking and dipping down then up to “confirm” there really was seagrass there. I don’t think I breathed and definitely did not even think about taking a selfie.

I was expecting to see lush fields of seagrass, just like a lawn of turf. Instead, what I saw was lots of sand with a brownish smudge that was the seagrass. But the easiest way to see the seagrass areas was to follow the dugong feeding trails. These were long lines in the sand that the dugongs had made shovelling up the seagrass to eat the whole plant straight out of the sand as they swam along.

After we’d mapped the area we then began the second job of recording the seagrass data (species, density). My task was to wait until the pilot was in position, just hovering above the sand/water and to carefully throw the sampler down for the scientist to then do the count for the research assistant to record. But the sampler is tied by rope which was only inches shorter than the distance to the rear propeller so I couldn’t muck around with lowering/retrieving. Hanging out of the door (trusting my seatbelt), barely touching my toe on the skid I quickly dropped the sampler three times along the sand to complete the monitoring at several spots along transects covering the whole area we’d just mapped.

With the light fading, feeling cold and numb the pilot asked after our last run whether we’d finished. The scientist decided he wanted to check one last area on Aquila Island. The pilot said it had better be quick as we didn’t have a lot of fuel left and off we sped to finish in record time.

It was honestly the most exhilarating flying experience I have ever had and definitely the best way to research and take samples over such a large area that couldn’t be accessed by boat. When we got out the pilot asked if I was alright and if I enjoyed myself; I didn’t know where to start. And for those that know me, I did not speak for the full 3.5 hours of flying – seriously!

But in answer to the pilot’s question, I definitely enjoyed the experience and am extremely proud of DBCT for sponsoring such important research for our generation and those to come, to make sure our Great Barrier Reef remains great!